Exhibition

Intermedia Theater

Jun 27, 2015 ― Jan 17, 2016

Venue

Nam June Paik Art Center, Gallery 1

Artists

Nam June Paik, Dick Higgins, Manfred Leve, Peter Moore, Ben Patterson, Ben Vautier

Curator

Sooyoung Lee

(Then) Some specific frustrations caused by cybernated life, require accordingly cybernated shock and catharsis.

-Nam June Paik

Few artists of our age used as many media as Nam June Paik—or, perhaps more accurately, worked “between” as many media. Paik was an artist who developed an intermedial approach, emphasizing not a single, pure medium but the dialectic between media. In the exhibition titled Intermedia Theatre, Nam June Paik Art Center presents the arena where art media and life media collide with each other— where Paik would be the most dramatic actor. He draws a line on the floor with his head, smashes a violin in a single blow, and creates a beautiful sound by destroying a piano. The narratives he makes from music unfold with boring everyday life, shocking violence and accidents and, above all things, humor. The solution for his art and life is always found in intermedia, even in spite of the emergence of various unexpected technologies. He puts happening in video and video in laser.

In this theatre, Paik invades the safe distance the audience puts between itself and the stage; a safe appreciation is no longer possible. The artist brings a new variable into our life, whispering to us to try to mix whatever media we have and manipulate space and time. This is how a Paik-style catharsis turns out to be of great use for “spiritual maturity.”

Hosted and Organized by

Nam June Paik Art Center, Gyeonggi Cultural Foundation

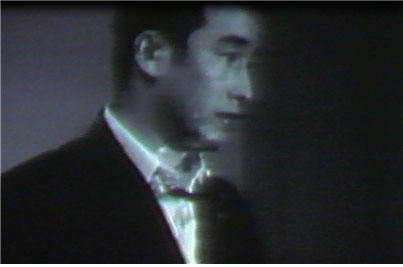

Nam June Paik, Zen for Head

La Monte Young, an American avant-garde artist and minimalist composer, released his famous Composition series in 1960. He emphasized the player’s performance by instructing non-musical activities such as making a fire or setting a butterfly free in Composition 1960. In particular, Composition 1961 is composed of the instruction, “draw a straight line and follow it.” and Nam June Paik responded to it with bodily movement by dipping his head into an ink-filled bucket and used his hair as a brush to slowly draw a

line on paper on the floor. Paik called this performance Zen for Head, and the impressive line, the result of the performance, was left as a visual product which shows from his fine movements to his powerful presence and actions. A text (composition), a performance, and a visual work readily share their own territory, creating the most intermedia link.

Peter Moore, Zen for Film

Zen for Film begins from a palm-sized plastic Fluxus box. When you open it, you will find a transparent film loop and a nail. After scratching the film with the nail and running it through a projector, the audience watches the most boring, beautiful, empty movie. When

the scratches and dust particles twinkle on the screen, Zen for Film only reveals its presence through the materiality of a film through

which light passes.

In New Cinema Festival in 1964, Nam June Paik approached the screen to cast the shadow on it or lay beneath the screen to make shadows with his hands. Peter Moore took pictures of Paik’s performance given in front of this empty movie, enlarging the range in which the work oscillated between a performance and a document.

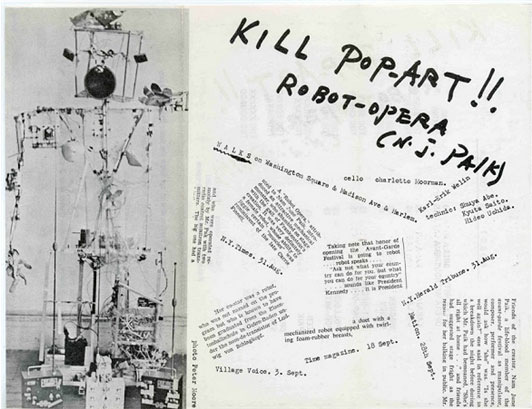

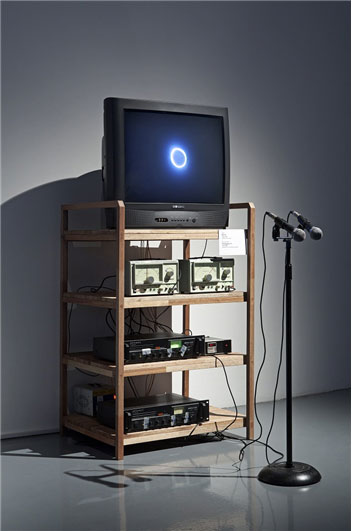

Nam June Paik, Robot Opera

Nam June Paik made continuous efforts to replace traditional musical instrumentation with non-musical media. Robot Opera(1965) was part of the second Annual New York Avant-garde Festival, in which Paik’s remote controlled robot performed with Moorman playing the cello. What the piece provided was not a mere participation of a robot in music; it was a fresh happening in which machinery and music coexisted instead of commercial and outdated traditional music.

Nam June Paik, Danger Music for Dick Higgins

Dick Higgins composed a series of works entitled Danger Music, composed of scores, since 1961. Danger music literally means an avant-garde form of music that can harm either the listener or the performer and therefore, can be even canceled by the performer before it is performed. Conceptually, it is often regarded as anti-music that goes against traditional music. Danger Music Number Five is a piece composed by Nam June Paik for Higgins, the famous

score of which directs the performer “creep into the vagina of a living whale.” Paik and Higgins’ Danger Music exists between various media, ranging from the imaginary sense of touch to a synesthetic sense, precariously or cheerfully.

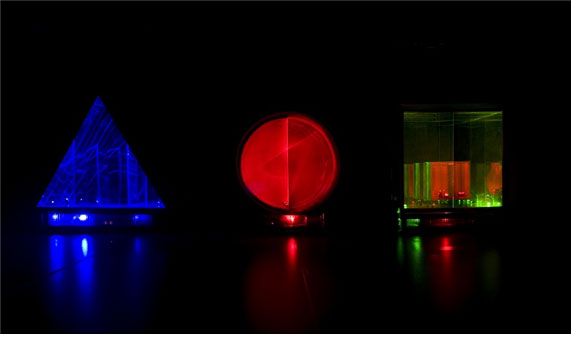

Nam June Paik, Three Elements

The laser works by Paik with which he experimented until his last moment could be called ‘post-video’ which lies in the extension of the theme that the artist pursued through video art, reorganizing space and time with the power of light and energy.

A laser beam moves constantly with a high speed and attracts our eyes to the infinite space and time. The patterns of various spaces

created by lasers are dynamic, mysterious, and beautiful. Lasers show a new possibility of space and time, that is, non-linear time and space with which Paik experimented throughout his lifetime, passing through various media from music and television to video.

Peter Moore, Stockhausen’s Originale: Doubletakes

Originale, meaning ‘odd people,’ is a music theatre piece by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. The intention of the

composer who was also a stage director of the premiere performance in 1961 in Cologne was to inspire various artists to perform their original actions freely and extemporaneously. A wide-range of characters are introduced: a pianist, a percussionist, a cameraman, a child, a fashion model, a newspaper seller, an animal attendant, a painter, a poet, and actors. Nam June Paik played a role of action

composer. It was not that Stockhausen gave autonomy to Paik, but that Paik could fully understand this form like the happening and perform freely, spontaneously and improvisationally. Originale has a lot of surreality and absurdity like Samuel Beckett’s theater since it combined a very strict form of Stockhausen’s serial music and a loose and impromptu structure of in the early happening art movement. And it also presents an archetype of the happening in which various media of various arts are played in a multi-synchronous way on the same stage.

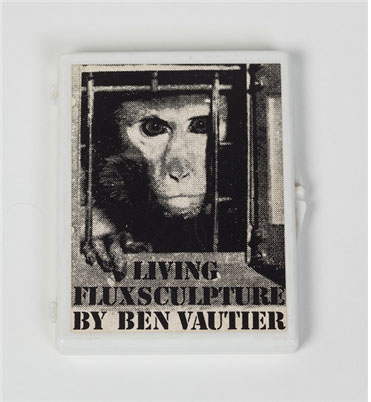

Ben Vautier, LIVING FLUXSCULPTURE

LIVING FLUXSCULPTURE (1966) by Ben Vautier has a picture of a monkey looking at the outside from behind bars, which is attached to a small plastic box. This box, which is in fact empty, allows more freedom and imagination when you open it. Flux or fluxus means in Latin ‘flow’ and is a name given to the most experimental and progressive art movement which emerged mainly in Germany and New York in the 1960s. From the beginning, the Fluxus movement involved various media including happening, performance, sculpture, poetry, and so on. Although the movement was titled and articulated by George Maciunas, it was a stream that was too diverse and free to come under a single category.

Nam June Paik was a leading figure in the 1960s Fluxus movement. Fluxus was the root of his artistic sprit. In 1997, Paik planned a concert titled A Celebration of Arts without Borders in memory of the movement. Ben Patterson presented his new work, Message to Nam June Paik, in the Nam June Paik Art Center in 2010. The ‘living fluxus’ running through the borders between our life and arts is still in effect.

Nam June Paik, Participation TV

In Nam June Paik’s Symphonie for 20 Rooms, the listeners are surrounded by synesthetic stimulations, including sight, hearing, touch, and even smell, created by various media such as sounds, lights, music composed using a tape recorder, a strong wind, a hot frying pan, and a mysterious perfume. In particular, ‘Fortissimo Cellar,’ completed with the participation of the audience who could make sound by stepping on a metal platform, reminds one of Participation TV presented in Paik’s first solo exhibition two years later. Paik may have imagined a platform which would be huge enough for the audience to jump on it and send the vibration to an amplifier to create a loud sound. When this idea met the new medium of TV, it was remediated as Participation TV in which the viewers could change the image on the screen by pedaling. In this way, Paik revisited his past artistic repertory with a new medium and

made it reborn as a new work of art.

Nam June Paik, Elephant Cart

Paik placed as many communication devices as he could remember, such as antique television sets, radios, telephones, and gramophone speakers, on a big cart with the sitting Buddha pulled by an elephant. The artist intentionally put new TV sets produced in the 1990s in the cases of antique TV sets, making them looking old. These camouflaged TVs showed films on elephants: fast-cut clips of

taming wild elephants, riding them for tourism purposes, and selling elephant statues in the Surin Elephant Roundup festival in Thailand.

It seems that the cart filled with televisions and radios will disseminate information along the direction where the elephant goes. This assemblage of old objects and new media makes the viewers reflect back on the past days in this age of speed when all things change rapidly, and reconsider the ways of today’s communication.

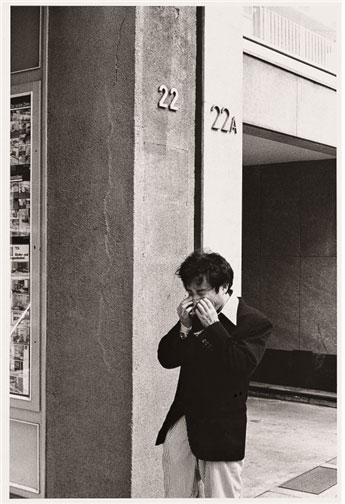

Manfred Leve, Hommage à Jean-Pierre Wilhelm

Walking, running, looking at passersby, pondering, and smiling… Nam June Paik asked Manfred Leve to take photographs of those seemingly meaningless actions. The venue was where Galerie 22 used to be the gallery where Paik’s Hommage à John Cage was first shown. At that time, the twenty-five-year-old Paik was unsuccessfully striving to take the opportunity to premiere his first composition at the International Summer Course for New Music in Darmstadt. It was Jean-Pierre Wilhelm, the owner of Galerie 22, who stretched the hand of help to this disappointed young artist. Since then, Wilhelm became a powerful patron for Fluxus artists including Paik. After ten years had passed since Wilhelm died, Paik memorialized him with the most common everyday behaviors. In the moment when the media of life and of art were unified as one, Paik himself became the most meaningful intermedia.